Clinical Question: What are the most effective evaluation and intervention techniques for treating sacroiliac joint dysfunction?

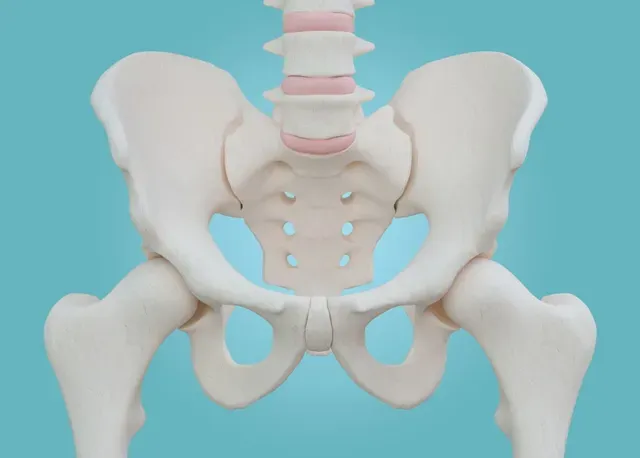

Background: Sacroiliac joint (SIJ) dysfunction is implicated in 10-30% of patients with low back pain (LBP) and during pregnancy up to 80% of women experience LBP/posterior pelvic pain arising from the SIJ. SIJ pain may disrupt normal kinematics of the low back and hip, leading to reduced muscle strength and endurance, impaired coordination/muscle recruitment, compromised gait pattern and transfer mechanics; all of which are associated with increased joint degeneration over time, decreased balance, and increased fall risk.

PICO:

Population: Individuals with SI joint dysfunction

Intervention: Manual therapy with therapeutic exercise

Comparison: Compare neuromuscular re-education/ther ex combined with manipulative therapy vs either intervention alone

Outcome desired: Reduction of pain, correction of antalgic gait, improved scores on objective and subjective outcome measures.

Article 1: Sacroiliac Joint Dysfunction: Evaluation & Management (Systematic Lit Review)(1)

Eval: Complicated by associated spinal lesions – 336 patients with SIJ dysfunction, 39% had an associated spinal disorder, among those, 41% had facet joint syndrome, 29% had spondylolisthesis.

Physical exam/clinical tests:

Due to limited reliability and validity of SIJ special tests, it’s important to use a combination of tests.

- Point specific tenderness over sacral sulcus & PSIS

- Combination of Gaenslen test, FABER test, and POSH (thigh thrust) have a reliability of >80%

- Combo of FABER, POSH, and REAB (resisted abduction) tests is also clinically acceptable (specificity of 100%, sensitivity 70-80%)

Article 2: Individuals with sacroiliac joint dysfunction display asymmetrical gait and a depressed synergy between muscles providing sacroiliac joint force closure when walking (2)

In 2012, Vleeming et al. introduced the principles of form and force closure relative to the SI joint. Form closure is the stability provided by the arthrokinematics between the iliac and sacral surfaces (varies widely among individuals) while force closure refers to the function of the ligaments and muscles acting across the SIJ to provide joint mobility and stability. One notable component of force closure that can be treated and improved in physical therapy is the connection between the ipsilateral gluteus maximus and the contralateral latissimus dorsi through the thoracolumbar fascia. Tension in these muscles increases tension in the thoracolumbar fascia and may help regulate forces and increase stability at the SIJ. This implies that it may be advantageous to have a muscle synergy between these two muscles during functional activity, specifically walking.

The study I am reviewing by Feeney et al. explored this relationship using surface EMGs during walking.

Results: Similar to previous findings, there was a synergy between glute max and contra latissimus dorsi. The glute max and contra lat synergy in participants with SIJ dysfunction was significantly depressed. Compared to the control group, participants with SIJ dysfunction also demonstrated greater asymmetries in hip extension and ground reaction forces between sides during walking.

Discussion: These findings are consistent with several previous studies; for example, Barker et al (2014) found that 70% of the force generated by glute max acts perpendicular to the plane of the SIJ with 14% of the force transmitted through the attachment to the thoracolumbar fascia. Carvalhais et al (2013) found that active and passive tensioning of the latissimus dorsi caused lateral rotation of the contralateral hip. Van Wingerden et al (2004) found that glute max activation significantly contributes to force closure by compressing the SIJ and preventing excessive shear forces that likely contribute to pain.

Chuckle’s Takeaway: Gute max and contralateral latissimus dorsi work together to keep the SIJ stable and prevent excessive shear force. When someone has a SIJ injury, like a unilateral loading injury, dashboard injury during MVA, or pregnancy related SIJ dysfunction, the pain & fear avoidance behavior alters reflexive pathways and disrupts the synergy between the glute max and lats. Acutely, this may help relieve pain by reducing compressive forces on the SIJ, however this disrupted muscle synergy leads to abnormal biomechanics which increase shear forces at the SIJ leading to impaired healing and chronic pain and dysfunction. A skilled physical therapy program should include relative rest and avoidance of unilateral loading during the acute phase to avoid learned non-use of the glute max/lat synergy. Following the acute phase, the glute max and lat should be trained to fire together to protect the SIJ and reduce shearing forces which will decrease pain and irritation of the tissues, promote proper healing, and reduce the risk of developing chronic SIJ pain. Most of our patients present in the chronic phase so most patients will have already developed learned non use of this synergy. We must find a targeted neuromuscular re-education program that will retrain the glute max/lat synergy for these patients to reduce unnecessary shear forces at the SIJ and reduce their symptoms. We should also assess the flexibility of these muscles, since increased tightness may lead to excessive compressive force, abnormal biomechanics, and increased pain.

Strengths: contributes to the body of knowledge of how SIJ pain leads to altered biomechanics, muscle recruitment, and joint kinematics which may lead to the development of targeted rehab programs.

Weaknesses: surface EMGs may not be valid. Small sample size (6 in each group) and only female participants (maybe a strength because 70% of SIJ dysfunction involves females, however the findings cannot be generalized to males). Discusses how pain leads to imbalances in kinematics and muscle recruitment but does not suggest ways to resolve the pain.

Chuckle’s Potential NMR exercises for retraining the glute max/contra lat synergy: Phase 1: bridge c B lat iso (drive arms into ground); Phase 2: Single leg bridge c glute activation & contralateral lat iso (driving arm into ground); Phase 3: Standing: lat pulldown c squat??? Brainstorm session!!

Article 3: Effectiveness of Exercise Therapy and Manipulation on Sacroiliac Joint Dysfunction: A Randomized Controlled Trial (3)

Methods: 51 patients with chronic SIJ dysfunction. 12 men, 39 women, mean age of 46.8 yrs.

Group 1: Exercise Therapy (ET group)

- Self mobilization exercises: posterior innominate self mob in supine. Grasp behind flexed knee and gently move it toward the trunk which rocks the innominate in a posterior direction relative to sacrum.

- SIJ stretches: “These exercises were performed in both right sidelying and left side-lying positions. The patient was in the side-lying position, with the upper hip being flexed 70 to 80 degrees and the knee flexed about 90 degrees. The patient’s trunk was then rotated toward the upper side as far as was comfortable. The patient was instructed to lift the top leg into hip abduction and internal rotation and resist the researcher or the partner for 5 seconds. The patient was instructed to breathe and exhale as the trainer gently over-pressured the trunk rotation. The patient was then instructed to relax the hip and leg and allow the leg to drop toward the floor. As the patient relaxed, a gentle overpressure was applied to the foot as the patient was allowing the hip and leg to drop further to the floor. This exercise was done 5 times a day with 2 minutes of rest between the sequences.”

- Spinal stabilization exercises: “These exercises were in four phases. Each new phase began every three weeks. Phase 1 – Supine abdominal draw-in – Abdominal draw-in, with one knee drawn to the chest – Abdominal draw-in, with the heels sliding backward one after the other – Abdominal draw-in, with both knees drawn to the chest – Supine twist – Prone bridging on elbows – Side bridging on elbows – Prone cobra – Quadruped opposite arm-leg lift Phase 2 – Abdominal draw-in with feet on the medicine ball plus abdominal draw-in with feet on the ball and added movement – Prone bridging on elbows with single-leg hip extension – Quadruped opposite arm-leg lifts, with cuff or dumbbell weights Phase 3 – Prone bridging, with the feet on the ball – Side bridging with single-leg hip abduction – Quadruped opposite arm-leg lifts on “half foam rollers” – Twisting while seated on medicine ball Phase 4 The exercises in Phase 4 were performed dynamically, meaning that the therapist threw a soccer ball-size medicine ball to the patient who was trying to stay in the position pertinent to the exercises in Phase 3.” Exercises performed 10x daily. Visit therapist once a week for first 12 weeks to perform exercise under supervision. Then independent until week 24.

Group 2: Manipulation therapy (MT)

- 2 manual maneuvers of posterior innominate rotation were performed on the first day of the study and then refer back to the therapist at designated follow up times.

- Posterior innominate mobilization (low velocity, low amplitude)

- SIJ manipulation HVLAT

- They performed the standing forward flexion test and Gillett test before and after manipulations to test the effectiveness. Negative special tests following manipulations. If special tests were positive, they repeated them, if still positive, the patient was excluded from the study.

Group 3: combo (EMT)

- Manipulation performed first, then same exercises as ET group to be performed 10x daily. Visit a therapist once a week for the first 12 weeks to do exercises under supervision. Then independent until week 24.

Outcome measures: pain (VAS) and functionality (ODI & Roland-Morris back pain questionnaire, and TUG, self paced walk test). Evaluated at 6 weeks, 12 weeks, and 24 weeks.

Results:

ET vs MT

At week 6: MT better than ET in all outcome measures.

At week 12 & 24: ET was as effective as MT in two parameters (the objective functional tests) and more effective in the other outcome measures (VAS, ODI, Roland-Morris back pain questionnaire).

ET vs EMT:

At week 6: EMT had better results in subjective tests, VAS, and the TUG.

At week 12 & 24: no significant difference observed between ET and EMT in all measures.

MT vs EMT:

Adding exercise to manipulative therapy did not reduce pain however EMT group scored better on Roland Morris at week 6 and 12, ODI at week 6 and 24, and functional objective tests at week 12 and 24.

Discussion: Therapeutic effect of MT appears more significant after 6 weeks. After 12 weeks, the exercise therapy group had more remarkable results than manual therapy. After 24 weeks, there were no significant differences among all three groups. This demonstrates that a combination of exercise and manual therapy is no more effective than either interventions implemented separately.

Strength: compares exercise vs manual therapy vs combo

Weakness: no control group, no long term follow ups. No STM included with manual therapy group.

Chuckle’s Takeaway: During the first 6 weeks of treating a patient with SIJ dysfunction, it is useful to use manual therapy/joint mobilization and manipulation to bring them relief in the first 6 weeks. We can also implement and train the patient to perform a ther ex program independently during the first 6 weeks. Following that, the patient could potentially be discharged (as long as they demonstrate independence with the ther ex program). They should be instructed to continue the ther ex program at home or at a local gym for 6-18 more weeks. If they require supervision of a skilled therapist, they can continue coming to the clinic but it may not be necessary if they have the resources to perform the exercises independently outside the clinic.

Citations:

1. Sacroiliac Joint Dysfunction: Evaluation and Management. Accessed June 15, 2021.

https://oce-ovid-com.proxy.lib.wayne.edu/article/00002508-200509000-00011/HTML

2. Individuals with sacroiliac joint dysfunction display asymmetrical gait and a depressed

synergy between muscles providing sacroiliac joint force closure when walking- ClinicalKey. Accessed June 15, 2021. https://www-clinicalkey-com.proxy.lib.wayne.edu/#!/content/playContent/1-s2.0-S105064111 8302827?returnurl=https:%2F%2Flinkinghub.elsevier.com%2Fretrieve%2Fpii%2FS1050641 118302827%3Fshowall%3Dtrue&referrer=

3. Nejati P. Effectiveness of Exercise Therapy andManipulation on Sacroiliac Joint Dysfunction:A Randomized Controlled Trial. Pain Physician. 2019;1(22;1):53-61. doi:10.36076/ppj/2019.22.53